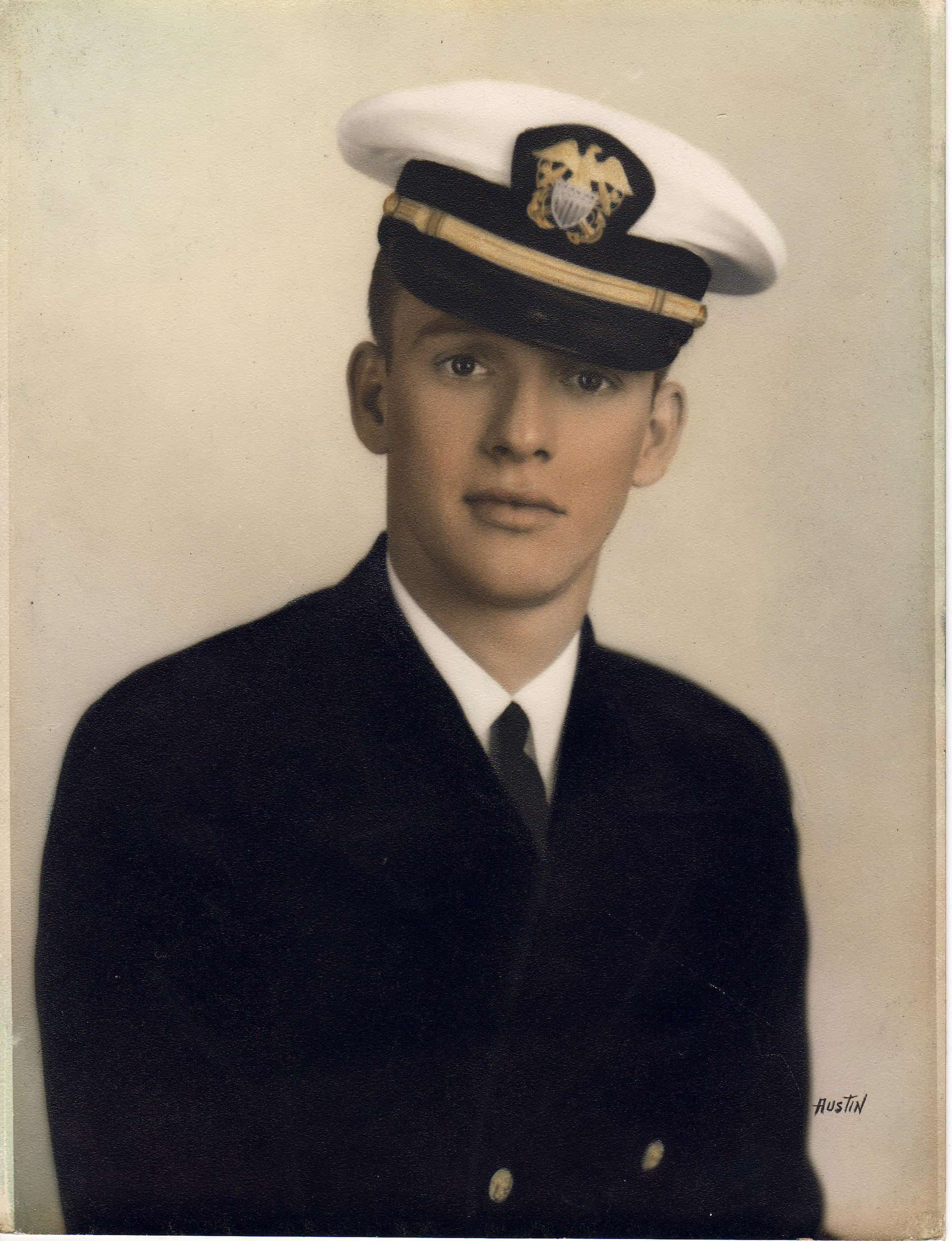

the glow from the Rectory’s beautiful Christmas tree is softly blending with the flicker from the fireplace . . . on my mind is a picture of my father taken the year I was born, his sword hangs beneath the mantle before me, the flag that draped his casket is displayed with that picture in the den upstairs.

I’m told there was a twinkle in his eyes and a smile on his face that day in 1939 when he was commissioned as an officer in the United States Navy . . . when I came along in 1943, both were gone – erased forever that Sunday morning in Pearl Harbor – my father was there aboard the USS Tangier. He survived; but he never talked about that horrific event, perhaps because to do so would have been to revisit his own funeral. You see, I believe the naive ensign who stood so tall on that sunny day in 1939 died in a matter of moments amidst the din of war without my ever having had the privilege of meeting him.

In the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, life had become very precious to my father; time was not to be wasted; self-discipline and self-support were virtues. As he believed, so I was taught. My father frequently paraphrased a line from The Sea Wolf by Jack London, telling me that a man is not a man until he can “walk alone between two sunrises and hustle the meat for his belly for three meals.” Such homespun wisdom was his way of preparing me to face the reality and rigors of life that ambushed him on the “day that will live in infamy.” My father was my best teacher; his classroom closed on Christmas Eve in 1983.

Get Involved with Our Ministries

One of the most important ways to get connected at The Church of the Cross is to first become a member of our congregation. If you are not a member and you are interested in learning more about membership, please call the Parish Office (843.757.2661) and speak to Sue.

Membership begins with an informal meeting with clergy. The next step in getting connected would be joining a Bible Study or small group to be in community with other Believers.

The Church of the Cross Locations

The Church of the Cross is situated across 3 distinct campuses. View our locations below: